–Darren Donate (from dialogist)

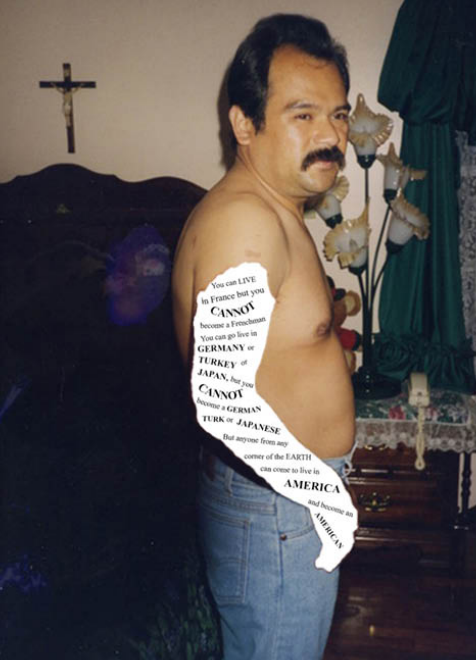

The first page of the shows a photograph of a man, the speaker’s father, with his right arm cut out from the center of the page. In the shape of the missing arm, text reads, “You can LIVE in FRANCE but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go live in GERMANY or TURKEY or JAPAN, but you CANNOT become a GERMAN TURK or JAPANESE. But anyone from any corner of the EARTH can come to live in AMERICA and become an AMERICAN.” The father stands without a shirt. He has a mustache and a cross hangs behind him on the wall, also a glass lamp and a curtain adorn the room behind him.

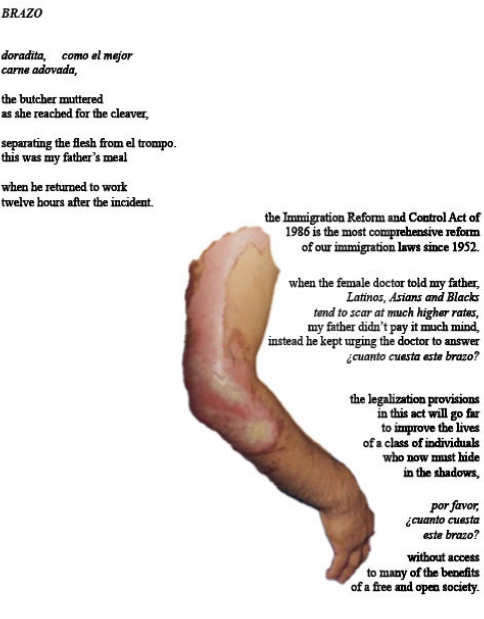

On the second page, the father’s arm appears badly burned or injured and the text around the image describes the speaker’s father’s burns, “the incident” at work. The top left reads, “BRAZO // doradita, [caesura] como el mejor / carne adovada, // the butcher muttered / as she reached for the cleaver, / separating the flesh from el trompo. / this was my father’s meal / when he returned to work / twelve hours after the incident.” The right side of the page reads, “The Immigration Reform and Control Act of / 1986 is the most comprehensive reform / of our immigration laws since 1952. // when the female doctor told my father, / Latinos, Asians and Blacks / tend to scar at much higher rates, / when my father didn’t pay it much mind, / instead he kept urging the doctor to answer ¿cuanto cuesta este brazo? // the legalization provisions / in this act will go far / to improve the lives / of a class of individuals / who now must hide / in the shadows, // por favor, / ¿cuanto cuesta / este brazo? // without access / to many of the benefits / of a free and open society.”

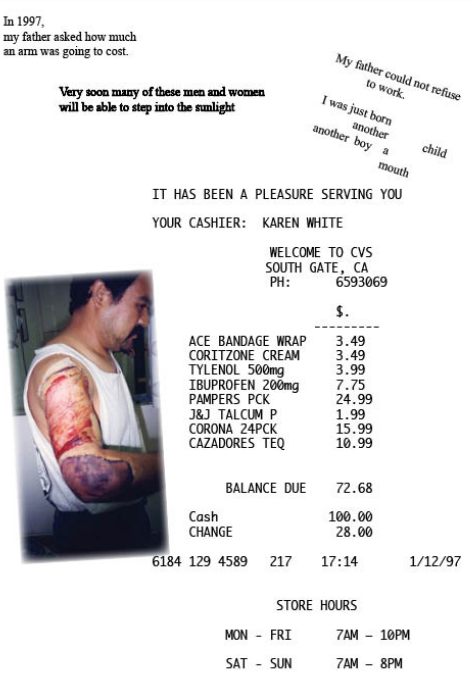

On the third page, many different pieces of poetry float above a cashier’s check from a CVS in South Gate, CA for Ace Bandage Wrap, cortizone cream, Tylenol, ibuprofen, pampers, J&J talcum p, Corona, Cazadores Teq, next to the image of the father and his burned arm. The top left of the page reads, “In 1997, / my father asked how much / an arm was going to cost.” Slightly below a bolder font reads, “Very soon many of these men and women / will be able to step into sunlight.” To the right reads, “My father could not refuse / to work. // I was born / another [caesura] child / another boy [caesura] a / mouth”.

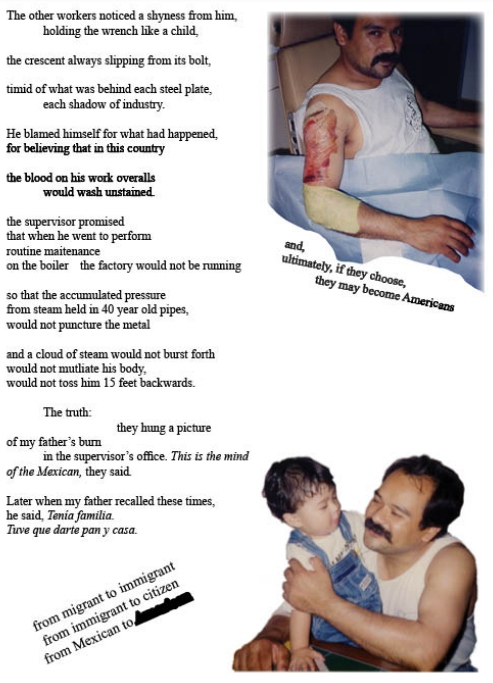

On the fourth page, the father sits on a chair. He wears a white tank top and his arm is partially bandaged. Underneath his arm, angled so that it matches the angle of his arm reads, “and / ultimately, if they choose, / they may become Americans”. The left side of the page reads, “The other workers noticed a shyness from him, / [caesura] holding the wrench like a child, // the crescent always slipping from its bolt, / timid of what was behind each steel plate, [caesura] each shadow of industry. // He blamed himself for what had happened, / for believing that in this country // the blood on his work overalls / [caesura] would wash unstained. // the supervisor promised / that when he went to perform / routine maintenance / on the boiler [caesura] the factory would not be running // so that the accumulated pressure / from steam held in 40 year old pipes, / would not puncture the metal // and a cloud of steam would not burst forth / would not mutilate his body, / would not toss him 15 feet backwards. // [caesura] The truth: / [caesura] they hung a picture / of my father’s burn / [caesura] in the supervisor’s office. This is the mind / of the Mexican, they said. // Later, when my father recalled these times, / he said, Tenía familia. / Tuve que darte pan y casa.” Below is a picture of the father holding a child. A tercet angled next to the image reads, “from migrant to immigrant / from immigrant to citizen / from Mexican to [blacked out]”.

On the fifth page, a small child’s head floats above a piece of tan grid paper. The top of the lined paper reads, “MONDAY – FRIDAY: 7-6 * SATURDAY: 8-5”. To the right side, is handwritten, “3/1/97.” The page is covered in handwritten Spanish and the bottom reads “Makita / IT’S ALL THE POWER YOU NEED,” a business logo. In the center of the page, the shape of the father’s arm from the first page is cut out. The white cut-out reads in small font, “And let me offer lesson number one about America: All great change in America begins at the dinner table. So, tomorrow night in the kitchen I hope the talking begins. And children, if your parents haven’t been teaching you what it means to be an American, let ’em know”.

The sixth page reads, “this is the price we pay / for wanting something better, / he used to say.” Another stanza is angled below it. The words look slightly wobbly, “Future generations of Americans will be thankful / for our efforts to humanely regain control / of our borders”. Below reads, “They threw him out of the factory / 1152 hours after the incident. / That is exactly 48 days. / He could not longer work / at the same rate with his injury. / On his last day of work / my father scribbled a letter to me, / in the best way a village boy could. / Now, as an adult, I see him / midiendo la palabra correcta, / [caesura] imaging how he torqued his / arm, dropping it into the right position, / bleeding into the thin / bandages / [caesura] and with his good hand / managing to contort his fingers / around a pen, some stolen work stationary, / telling me how lucky I was to be born / in this country, to be given this name.” Below text is slanted and slightly wobbly, “and thereby preserve the value / of one of the most sacred possessions / of our people: // American citizenship.”

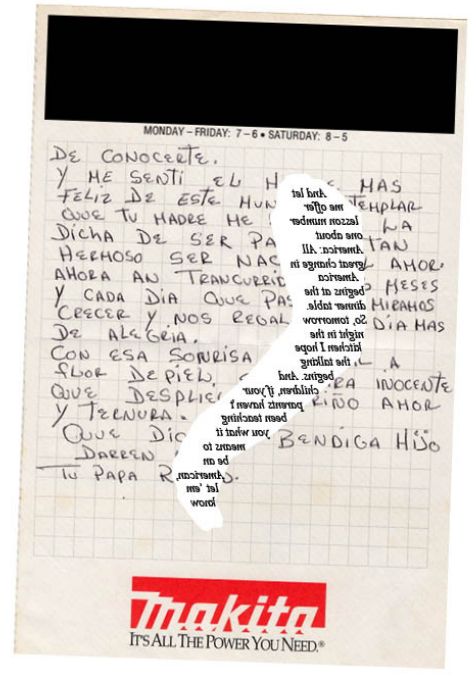

On the seventh page, another piece of tan grid paper with “MONDAY – FRIDAY: 7-6 * SATURDAY: 8-5” on the top. The page is covered in handwritten Spanish and the bottom reads “Makita / IT’S ALL THE POWER YOU NEED,” a business logo. The handwritten message ends, “Tu Papa [unreadable]”. In the center, the shape of the father’s arm from the first page is flipped, and the text from the fifth page remains in the arm, but mirrored, so that it can only be read backward.